Part 1: Basic Moves

My aim in writing this is two-fold: One, to share some ideas, because a lot of great conversations about the AW format have gotten buried in various places all over the interwebs and aren’t easily to look up for people new to it. Two, maybe to start some conversation up again, because I’m not finished writing rules in this vein and new ideas are always good to see.

So anyway, back at the dawn of time, Apocalypse World had the move “when you seduce or manipulate someone, roll+hot” in it. And that was your move for doing the social stuff and then rolling dice for it.

Asymmetrical Effects

Right, so the move works differently on PCs and NPCs. Your influence over NPCs depends on your hot stat and your rolls, not so much on the individual NPC (barring custom moves). Your influence over PCs isn’t absolute, though. You can’t make another PC do something, you can only put pressure on the player through rules-based incentives that model the character’s experience of being socially pressured. This is good if you want to really highlight the fact that PCs and NPCs use different rules, but isn’t particularly elegant. It looks more like two moves than only one.

However, the versions of this move in Dungeon World and Monsterhearts only work on NPCs, because Monsterhearts has other ways to pressure PCs (strings and conditions), and Dungeon World simply isn’t about using the rules to persuade the other PCs.

Monsterhearts actually paves the way for unifying both PC and NPC versions into one move, with advantage and disadvantage. If the move works the same, but you can offer advantage or impose disadvantage, PCs are free to make their choices and the rules for NPC might allow them to refuse in a few, limited circumstances, but overall mandates they behave as expected. The problem here is to work out how the concrete assurances of the 7-9 result play out when PCs ask for them. How much can a PC ask for, anyway?

Wording and Leverage

The versions in both AW and DW both require an explanation of leverage, which (in my opinion) fights with the actual trigger wording, and perhaps makes it redundant and unnecessary except for purposes of a style and consistency (in that every move should have a similarly-worded trigger). Certainly “manipulate someone” is terribly vague and even though “use your leverage over someone to make them do what you want” is long and cumbersome, it does a much better job at explaining what is really happening. It leaves out seduce, however, and that’s an important part of AW, so you can sort of see why it’s that way.

A problem I’ve seen here is that people write special moves referencing leverage, like “you can always use the threat of being beaten up by you as leverage.” This means either that even NPCs who cannot feel fear and ghosts that the character cannot even touch are always afraid of being beaten up by him (unless perhaps the player rolls a 6 or less), or that it’s just a suggestion to the GM to include NPCs that are afraid of being beaten up by this character. If it’s just a suggestion, it should be worded that way, and not as an absolute rule; and as an absolute rule, it has the potential to make absolutely no sense. Not that it’s exactly easy to write a good, snappy alternative (aside from just limiting those affected), and I haven’t seen one yet.

It’s possible for vagueness like that to work in your favour, though. In some cases, it’s quite alright to simply let the people playing the game interpret the trigger wording. Monsterhearts, for example, doesn’t define what manipulating an NPC actually is, it just says you have to actually want something from them. In Throne of Dooms, I went with the trigger “when you try to talk someone into something.” Although there’s some explanation, the move assumes the conversation has already started and the PC’s desired outcome might actually happen, there’s just no certainty. But that game’s a work in progress—the move has changed before and it might change again. In both cases, a sense of the game’s genre is pretty crucial to understanding the move’s trigger. This is true of most Monsterhearts moves—run away works as a basic move, but would seem both oddly specific and opposed to the genre in a game like Dungeon World.

Information-Gathering Social Moves

In the Seclusium of Orphone and Apocalypse World: Dark Ages, there are social moves that let you collect information by asking questions, the same as when you read a sitch or discern realities. John Harper distilled these down to a question-less move in a recent g+ post:

When you manipulate someone to get what you want, roll+[stat] and they’ll name the price. On a 10+, they name the absolute minimum price they’d possibly accept. On a 7-9, they name a price they could live with. On a 6-, they name any price they want.

Essentially, where the AW manipulate moves and those like it allow you to make demands of the fiction, these moves allow you to interrogate it in order to find out what you need to do in the fiction to make something happen. One advantage is that this works equally well on both PCs and NPCs, but it can feel strange right next to more typical perception moves, if players perceive social influence as an active force more than a matter of reading people. I used a hybrid version in Evil of the Stars, stealing the move trigger from AW:DA to finally finish he interview move that’s been kicking around the development of my sci-fi games for several years now:

When you draw someone out in conversation, roll+hot. On a 12+, both. On a 10-11, choose 1:

· Ask 2 questions from the list below.

· Say how you make them feel.

On a 7-9, ask 1:

· How could I get your character to _____?

· Is your character being truthful?

· What does your character intend to do?

· What does your character want or expect from me?

· What is your character really feeling?

On a miss, ask 1 anyway, but they can also ask 2 of you.

Wording Again

It’s good to mess around with the wording of move triggers so they fit the game, the genre, and also your own play style. “Manipulate” isn’t quite the same as “talk someone into something,” and “draw someone out in conversation” is something else again. You want to push the players towards behaviours that support the genre and the style of play the game is supposed to be about, so put that in the move triggers. Here’s a different version of John’s questionless information-gathering move from above:

When you do someone a favour, then make a request of them, roll+stat. On a 10+, they must tell you the easiest way to get them to fulfill the request, or the lowest price they will accept in exchange. On a 7-9, they must name a price they are willing to live with. On a 6 or less, they can name any price they desire, or none, and the GM tells you the consequences.

So instead of manipulating people to get what you want, getting people to do things in this game is about reaching out to them first, building connections, and finding out what it would take to convince them. You bring the king some tribute first, and then you ask about redrawing the borders between your estates and the evil duke’s estates. Or you give the guards cigarettes, and then ask them to let you see the prisoner. You buy someone a drink, then see if they are willing to go home with you.

One of the social moves in Night Witches takes a cue from DW’s Defy Danger, and allows you to modify the dice using different stats based on how you Act Up:

When you try to get your way…

…by acting like a hooligan, roll+luck.

…by acting like a lady, roll+guts.

…by acting like a natural-born Soviet airwoman, roll+medals.

In most other AW hacks, using a different stat has been a matter of having a special stat-substitution move.

Scene Resolution

But the real innovation I saw in this Night Witches move was when the wording in an earlier draft including the words “cause a scene.” In a game with heavy, and especially regimented, scene-framing rules, this can encourage players to frame a scene already in the process of making this move. Because the results of Act Up are broader than simply influencing a single person, the way moves derived from seduce or manipulate are, it can function as either resolution for a single action in a larger scene, or for a whole scene itself.

On a 10+, choose two. On a 7-9, choose one:

· Make someone do what you want.

· Ensure that there are no consequences for Acting Up.

· Add one to the Mission Pool.

Imagine a Monsterhearts style game with a similar move, where Marcia the scheming vampire throws a birthday party for Clarice (“when you do something nice for someone, roll+hot”), rolls well for the move, and chooses two options. Marcia seduces Keith (Clarice’s boyfriend) as one, and puts the condition “Owes Marcia” on Clarice as the other. As you can see, she didn’t even use the move against Keith, but since he was there in the scene, fair is fair. Not every genre can use this, but for a lot that can, it’s basically half-way there already.

And Now For Something Completely Different

Or if you like the idea of a game that runs entirely on the workspace rules, instead of rolling 2d6 all the time, you can have information-gathering moves without the dice:

When you try to manipulate someone in order to get your way, the GM will tell you what it will take (1 to 4 of the following):

· First you must __________.

· It’ll take (hours/days/weeks) to convince them.

· They want to get paid.

· They’ll only do part of what you want, if someone else does the rest.

· You must keep __________ out of it.

· You’ll need help to convince them, from __________.

So that’s a bunch of stuff, but it doesn’t cover things like Hx, bonds, aid and interfere, and currencies like hold, strings, and debts. Maybe I’ll cover that in Part 2 and maybe I’ll just slack off and not.

edit

Additional Commentary:

Rob Brennan pointed out the interplay between social influence and the perception moves. In AW, you don’t usually go looking to seduce or manipulate without knowing you have leverage—either you know they want something, because it’s clear in the fiction, or you use the read a person move to find out.

In cases where you ask questions, the general idea is that this occurs between players, and that the information is conveyed to the PC through any and all means available, which can include the characters talking exactly like the players, or can be (in the fiction) entirely non-verbal. This can be expressed in phrasing the questions to the player (“What is your character really feeling”), but could also maybe be explained in a paragraph somewhere if the game you are writing is marketed towards people who aren’t AW vets.

I thought about playing around with triggers to achieve a completely different effect and came up with this one:

When you pretend you’re something you’re not, in order to deceive an enemy, roll+[stat]. On a 10+, they take you at your word. On a 7-9, they require concrete proof before they believe your lies.

Here’s a test for you: Why is there a second clause (“in order to deceive an enemy”) in that trigger?

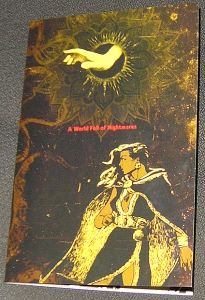

I wrote a short supplement for The Nightmares Underneath that has Powered by the Apocalypse rules for players to use, for those of you who prefer that style over the old school D&D-ish rules. It is called A World Full of Nightmares, and it includes:

I wrote a short supplement for The Nightmares Underneath that has Powered by the Apocalypse rules for players to use, for those of you who prefer that style over the old school D&D-ish rules. It is called A World Full of Nightmares, and it includes: